General Information

Population

Immigration

Emigration

Working-age population

Unemployment rate

GDP

Refugees and IDPs

Citizenship

Territory

Migration Authorities

Responsible Body

Line Ministries

Agencies

Description

For the past thirty years, Estonia has been a country of emigration. However, since 2015, the immigration flow has been steadily growing thereby resulting in a positive net migration, which has also been driving population growth against the negative natural increase. On 31 December 2021, 1.331.824 people lived permanently in Estonia, which is 2.9% more than ten years ago.

In 2015, 15.413 people left the country, while 13.003 entered it. The number of immigrants peaked at 19.524 persons in 2021. Meanwhile, the number of emigrants has been declining slowly in recent years, reaching 12.481 people in 2021. The shrinking of the population in the primary migration age (20-40) leads to the decline in migration potential of the country and affects out-migration.

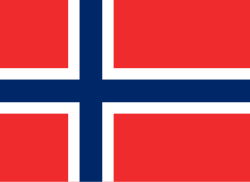

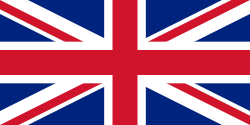

Emigration from Estonia in the 1990s mainly consisted of returning minority populations – mostly Russian speaking – to their former homelands. With Estonia joining the EU in 2004, the emigration pattern changed in favour of older EU member states and then further intensified after the economic recession in 2008. The most important destination for Estonians is neighbouring Finland that attracts emigrants due to its geographical proximity and comparative economic prosperity. In the period between 2004 and 2021, Finland attracted over one-third of all emigrants from Estonia. According to Statistics Finland, 51.805 Estonians were living in Finland in 2021, constituting the largest Estonian migrant community in the world. While it is easy to commute between the two countries, many Estonians also live and work in Finland temporarily. Historically, Russia, Sweden, USA and Canada hosted large Estonian communities. The same countries, but also the UK, Germany and Australia represent important destinations for new migrants from Estonia. Westward migration tends to be temporary, associated with short periods of study and work abroad. Meanwhile, Eastward migration, i.e., to Russia, is often related to family reasons.

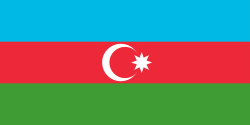

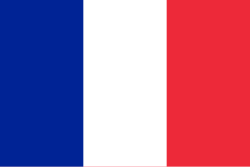

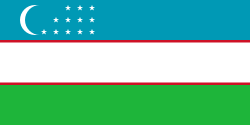

With the growth of welfare, the number of immigrants coming to Estonia has been on the rise. Estonian data shows that around 40% of all immigrants who arrived to Estonia in the past five years comprise Estonian citizens, most of whom are returning from Finland, Russia, and Great Britain. Among other EU citizens, the most numerous groups of immigrants who have registered their place of residence in Estonia come from Finland, Latvia, Germany and France. Migration from EU member states tends to be temporary for the reasons of studying and short-term employment. When it comes to non-EU nationals, the lion’s share has been coming from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus. For example, in 2021, 1924 Ukrainians, 1423 Russians and 437 Belarusians received first-time temporary residence permits in Estonia, representing a steady growth year on year. A large Russian-speaking community and infrastructure (such as schools, child-care, leisure facilities) that developed in Estonia in the Soviet period make Estonia an attractive destination for Russian speakers. Ethnic Russians comprise the largest group of people (51%) who hold valid long-term residence permits (77 579 individuals in 2021). Recipients of long-term residence permits also include persons with undetermined citizenship (holders of the so-called grey passport) who came to Estonia before 1 July 1990 and have continued to reside in Estonia (66 682 individuals in 2021). In addition, 4.249 Ukrainians and 1.214 Belarusians hold a valid long-term residence permit in 2021. Beyond the three above-mentioned non-EU countries, an increasing number of immigrants are arriving from Nigeria and India. The main reasons for immigration among non-EU nationals are work, family and education.

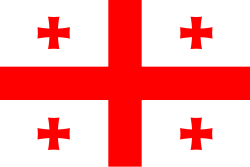

In terms of international protection, the flow of asylum seekers in Estonia has been inconsiderable. Between 2017 and 2021, the number of applicants did not exceed 200 persons per year and amounted to 76 persons in 2021. Since 1997, as many as 1327 foreigners have applied for international protection in Estonia, of whom 603 persons received either refugee status or subsidiary protection. The largest numbers of asylum seekers have arrived from Ukraine, Syria, Russia, Georgia and Afghanistan. During the period from 1997 to 2021, Syrians (199), Ukrainians (93) and Russians (66) were among the top recipients of international protection in Estonia.

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, the situation in terms of asylum has changed. As of 9 March 2022, a Decree of the Government of the Republic of Estonia entered into force, allowing citizens of Ukraine and their family members who have fled to Estonia to apply for temporary protection. They are entitled to a one-year residence permit that grants rights similar to those of Estonian residents, such as access to social services and the right to work and education. This category also has the right of free movement within the European Union. According to the Estonian Police and Border Guard data, as of 21 August, 32.210 people have applied for temporary protection in Estonia. Since 24 February 2022, another 995 people have applied in Estonia for international protection, including 792 Ukrainian citizens. In addition, the Estonian government has approved the sanction, which prevents Russian and Belarusian citizens from applying for temporary residence permits or visas for studying in Estonia. Besides, citizens of Russia and Belarus can register for short-term employment only if they have a valid visa issued by Estonia. From 18 August, new restrictions on entering Estonia apply to Russian citizens. The issuing of Estonian visas to Russian citizens has been limited, and Russian citizens holding a valid visa issued by Estonia and whose purpose of coming to Estonia is tourism, business, sports or culture are not allowed to enter the country.

There has also been an upward trend of irregular migration to Estonia, mainly associated with the misuse of the visa system (for example, when tourist visas are used for work). In 2021, out of the 335 refusals for entry at the external border, Russians received 79% of refusals, followed by nationals of Ukraine (5%), Belarus and Moldova. In the same year, no third-country nationals were identified as victims of trafficking in human beings, although there were 34 presumed THB victims: 62% of them were women, and 78% were involved in sexual exploitation; 27% were male, and 78% of them were involved in labour exploitation. Most of the presumed victims were citizens of Ukraine, Brazil and Columbia.

Immigration to Estonia is governed by the Aliens Act, which regulates the basis for the entry of foreign nationals into Estonia, their temporary stay, residence and employment. It also regulates the migration quota, which remains currently at 0.1 % of the resident population. In 2022, the quota has been set at 1.311. The quota mainly regulates labour and business migration from third countries. It does not apply to EU citizens and their family members, citizens of the US, the UK and Japan, as well as those seeking international protection. People coming to work in the IT field and start-ups, married spouses, students, and some academic staff are also excluded. In general, Estonian migration policy has been considered relatively strict due to its migration quota and bureaucratic procedures for residence permits. However, many changes towards the liberalisation of migration legislation have been taking place over the past years. Aliens Act has been amended several times simplifying procedures for foreign workers to arrive and work in Estonia. The last amendments also aim to simplify the entry of Ukrainian refugees of war into the labour market.

Because of the migratory pressure on Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland in 2021, the Estonian government decided to amend the State Borders Act allowing the state to better contain mass immigration in case of an emergency if foreigners cross the Estonian border illegally and submit unfounded applications for international protection. Accordingly, the Police and Border Guard Board may refuse to accept an application for international protection of an alien who has entered the country illegally and make them return without issuing a precept to leave or a decision to refuse entry.

In 2014, Estonia was the first country in the world to start offering e-residency or digital identity services to citizens of foreign countries to open an EU-based company but manage the business from anywhere in the world. While the e-resident status together with an e-resident digital ID card allows digital identification and enables foreigners to use Estonia’s e-state services remotely, the e-resident digital ID is not a physical identity or travel document nor does it grant citizenship, tax residence, a residence permit, or a permit to enter Estonia or the European Union. In 2021, the number of issued e-resident digital IDs increased by 8%. The total number of e-residents as of 31 December 2021 was 88.267. The majority of holders are Russian, Finnish, Ukrainian, German and Chinese nationals.

Estonia is a party to several migration dialogues, including the Prague Process.