General Information

Population

Immigration

Emigration

Working-age population

Unemployment rate

GDP

Refugees and IDPs

Citizenship

Territory

Migration Authorities

Responsible Body

Line Ministries

Agencies

Key Policy Documents

Immigration Act: Chapter 217 & its amendments (1970)

International Protection Act: Chapter 420 & its amendments (2001)

International Protection Agency (establishment) Order, Legal Notice 194 (2020)

Minor Protection (Alternative Care) Act: Chapter 602 & its amendments (2020)

Reception of Asylum-seekers Regulations, Legal Notice 320 & its amendments (2005)

Immigration Regulations, Legal Notice 205 & its amendments (2004)

Maltese Citizenship Act & its amendments (1964)

Migrant Integration Strategy & Action Plan – Vision (2020)

Policy regarding Specific Residence Authorisation (Updated policy, 2020)

Description

With an area of just over 300 square kilometres and a total population of 519.562 people, Malta is by far the most densely populated country in the European Union. Overpopulation, poverty and unemployment were the main push factors for emigration from Malta for decades. The picture began to turn around in the 1990s when Malta started receiving refugees from Iraq and the former Yugoslavian states. After Malta joined the EU in 2002, the number of refugees and migrants using Malta as a gateway to Europe increased significantly.

In the early 2020s, Malta is among the top three countries in the EU in terms of immigration and emigration rates. Each fifth person living in Malta is a foreigner. According to the 2021 national census, Malta hosted 115.449 migrants, accounting for 22.2 % of its total population, representing the highest share of non-nationals within the EU. Non-Maltese are predominantly males (68.481) and younger compared to their Maltese counterparts.

Malta’s economy boomed in recent years, particularly due to tourism, with the country’s GDP growth being significantly higher than the EU average and reaching 9.4% in 2021. The same year, the unemployment rate was 3.5% and the inflation rate stood at 1.5 %. The rapid growth of the Maltese economy necessitates demand for new workers. In 2020, within the EU, Malta recorded the highest self-employment share for persons born in another EU Member State (22.6 %) and the third highest self-employment share for persons born outside the EU (20.6 %).

By the end of 2020, there were 77.825 foreign nationals working legally in Malta. At the end of 2021, 44% of foreign workers in Malta came from the EU, primarily from Italy, and another 56% came from non-EU countries. For the past decade, most non-EU foreign workers came to Malta from the Philippines, Serbia and India. In terms of sectors, professional, scientific, technical, administration and support service activities one is the most popular both among the EU and non-EU workers.

In 2021, 61.885 foreigners had residence permits in the country, which is almost 30% more than in 2019. In the same year, 14.358 first-time residence permits were issued in Malta. Most of them were granted for employment reasons (8.060), followed by education (2.790) and family reasons (1.811). In terms of origin countries, most new permits were granted to citizens of India (1.714), Turkey (1.579), Albania (1.142), Philippines (939) and Serbia (791). Malta experienced a constant increase in immigration flows, which reached its peak of 28.341 in 2019. 20.070 of this number represented non-EU nationals. In 2020, the flow dropped to 13.885, presumably, due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

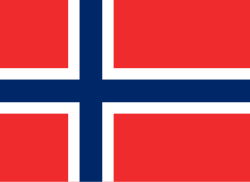

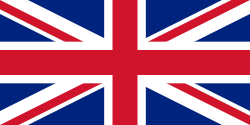

According to Eurostat between 2013 and 2020, 62.323 persons emigrated from Maltand the vast majority (53.703 persons) were foreigners, of whom 31.050 were non-EU citizens and 22.653 were EU nationals. The countries of traditional Maltese emigration include Australia, Canada, the UK and the US. After Malta’s accession to the EU, many Maltese settled in EU countries forming new diaspora communities. In 2020, according to UN DESA, 102.793 Maltese lived abroad. The top 10 countries that host Maltese diaspora are Australia (45.357), the UK (29.600), the US (12.154), Canada (8.037), Italy (1.984), Germany (931), Belgium (488), Netherlands (461) and France (442). Professional opportunities abroad represent the most important pull factor for people to leave the country. Notably, an increasing number of medical graduates have moved to the UK to finalize their specialization, often settling there permanently.

In terms of undocumented arrivals, from 2011 to 2021, 14.165 irregular migrants arrived by boat in Malta. Numbers grew from 2011 until 2013 but saw a constant decline thereafter. In 2017, only 20 migrants reached the Maltese shore. However, the arrivals considerably increased in the period 2018-2019, when Malta received 4.850 persons. In 2021, there have been 838 undocumented sea arrivals to Malta, which consists a decrease of 63% compared to 2020. The majority (81%) of the new arrivals comprised citizens of African countries, while the remaining 19.0% were citizens of Asian countries. The top countries of origin were Eritrea (26.3%), Syria (16%), Sudan (11.9%) and Egypt (11.5%).

International Protection procedures follow the same patterns. Over the past decade, 23.400 asylum applications were filed in Malta, with a maximum of 4.090 applications registered in 2019. In 2021, a total of 1.517 applications for international protection have been registered, a decrease of 38.9% compared to 2022. The recognition rate at first instance declined from 90.1% in 2012 to 22.2% in 2021. In recent years, the majority of asylum applications are lodged by citizens of Sudan, Syria, Libya, Bangladesh, Somalia and Eritrea.

In 2020 and 2021, close to 500 persons were relocated from Malta to other EU countries. Since 2019, relocations from Malta occur on an ad hoc basis within the non-binding, informal agreements with the other EU Member States. Moreover, 466 individuals returned home through voluntary repatriation programmes since 2009. In the period 2012-2021, 9.560 third-country nationals were ordered to leave Malta.

From the beginning of the war in Ukraine in February 2022 until May 2022, 1.002 persons who fled the war received temporary protection in Malta. Reports indicate that thus far there is no coordinated effort to implement the Temporary Protection Directive (2001/55/EC) and limited information is available on whether beneficiaries actually enjoy their rights as provided by the Directive.

On 7 August 2020, the International Protection Agency (IPA) replaced the previously operational Office of the Refugee Commissioner, mandated to receive, process and determine applications for international protection. While the IPA is responsible for examining and determining applications for international protection at first instance, the International Protection Appeals Tribunal (IPAT) examines appeals concerning rejected applications. At the same time, Malta amended its Refugees Act to align national legislation with the EU Directives, also yielding consequential amendments to the Procedural Standards for Granting and Withdrawing International Protection Regulations.

On 15 November 2018, Malta launched a Policy regarding Specific Residence Authorisation (SRA), which replaced the Temporary Humanitarian Protection New (THPN). Through this policy, Malta established a system aimed at addressing the situation of THPN certificate holders and other persons who do not have international protection but cannot return to their country of origin. In November 2020, Malta updated the SRA Policy, an amendment that has been criticised by local NGOs for creating serious obstacles to the legalization of people and for having a dramatic impact on many SRA holders who failed to renew their status in time. In 2021, in an OHCHR report covering the period 2019- 2020, various allegations of delays in assisting migrant vessels in distress, as well as incidents of migrant vessels being turned away by European authorities in the central Mediterranean Sea, were reported. Armed Forces of Malta were accused of refusing to allow migrants in distress to arrive in Malta.

Malta is a party to several Migration Dialogues, including the Budapest Process, the Prague Process, the Rabat Process and the Mediterranean Transit Migration (MTM).

Relevant Publications